Free Will in a Lawful Universe

Many wonder whether we truly choose our actions or if nature’s laws pre-decide everything. These concepts needn’t conflict—even in a world that might be fully governed by cause-and-effect

TL;DR

Many people wonder, do we have free will or are we at the whims of the universe’s physical laws? This is the wrong framing. Determinism needn’t erase our sense of agency; in fact, your deliberations, desires, and choices are precisely how the future unfolds. The key is recognizing that you aren't in a tug-of-war against "physical law"—you are part of the lawful chain that shapes tomorrow.. Even if the universe unfolds according to strict cause-and-effect, that cause-and-effect includes your mental process of weighing options, responding to reasons, and deciding what to do. Randomness wouldn’t strengthen your control—if anything, it would introduce outcomes you didn’t select. By seeing yourself as embedded in physics rather than constrained by it, you reclaim the idea that your effort truly matters: if you didn’t form intentions, those outcomes simply wouldn’t happen. In that sense, “free will” is compatible with a determined world; it’s the name we give to our very real power to steer what happens next, from inside the flow of nature itself.

Overcoming Determinism Anxiety to find Free Will

I remember just before starting college I began grappling with the idea that everything in the universe might be fully determined. The strong stance for determinism supports, in principle, that perfect knowledge of the physical state at the Big Bang could predict every future state of the universe. This is fascinating but also deeply unsettling. If all my future choices are somehow “already written” into the fabric of reality, where is my freedom in any of this? Do I have any agency? I think this is a topic that’s crucial to resolve properly. I imagine a vast majority of people think about this and come to a sort of roadblock about whether we have free will. I see so many people striking a false dichotomy between free will and determinism; it’s an easy mistake and one that significantly affected my experience for a substantial amount of time.

For at least 2-3 years the concept of determinism played a big part in robbing me of motivation (among other things). I couldn’t shake the question: “Why bother making plans or pushing myself to achieve anything if it’s all locked in anyway?” For instance, if you are deciding whether to spend your weekend studying a new language, you might think, What difference does it make? If the universe’s trajectory is fixed, you’re either fated to do it or you’re not. This line of thinking can sap your willpower. It feels like cheating to motivate yourself—trying to pretend you have real control, despite a suspicion that you simply cannot.

There’s a post on LessWrong describing the exact same sense of “demotivation and pointlessness,” explaining how it’s tough to keep trying when you believe your life is preordained. I share this because for many people, the leap from “everything follows from prior physical states” to “I have no real agency” feels totally natural. For others, it’s hard to imagine why determinism would upset anyone at all. But if you’re wired like me—and like that online poster—then you know how easy it is to spin into a kind of existential spiral: you look around and think, All these struggles and goals are just illusions; the outcome was set from the start. With no overarching framework to reconcile determinism with my sense of personal effort, I ended up feeling powerless.

Here’s the good news: that powerless feeling is based on a misunderstanding—one that I (and many others) stumbled into. Over the years, I’ve come to realize you can take determinism seriously while still embracing a robust sense of “free will”—or whatever we choose to call the human capacity for choice and effort. I’ll walk through the key ideas, insights, and analogies that helped me climb out of the demotivated pit, with the biggest conceptual shifts thanks to a series of writings by Eliezer Yudkowsky (this was my encounter, but there are deep historical lines of philosophical thought in this realm obviously!) This perspective aligns with what philosophers call "compatibilism” and it doesn’t claim to be the definitive solution to every free will puzzle—but it’s a powerful and practical way to dissolve the sense of dread around it.

What I Mean by “Free Will”

In this piece, I’m using “free will” in a compatibilist sense: the idea that our actions can be genuinely ours—even if they arise from a lawful, cause-and-effect universe. Specifically, free will here refers to the fact that our conscious deliberation, our reasons, and our desires make a real difference in shaping what happens next. If your beliefs or intentions were different, your resulting actions would likely be different, too. This doesn’t require “breaking” the physical laws or positing supernatural magic. Rather, it says the laws of nature include your capacity to choose based on reasons, weigh possibilities, and see those deliberations reflected in the ultimate outcome. Philosophers call this compatibilism because it treats robust agency as fully compatible with an orderly, law-governed reality.

Determinism Doesn’t Have to Kill Motivation

Here’s a concise response by Carl Feynman (Richard Feynman’s son!) to the poster’s dilemma about free will vs. determinism that clarifies why there isn’t necessarily an incompatibility. He suggests that determinism doesn’t negate our sense of agency but in fact requires it. To paraphrase his central idea:

Sure, the universe might be deterministic, but that doesn’t mean you can bypass the ‘decision process’ in your brain. Going through the mental algorithm - wanting something and intending to do it - is exactly how your next action gets decided. Intention isn’t an extra add-on; it’s part of the causal chain.

This is a critical shift in perspective. Instead of seeing determinism as a cosmic puppet-master forcing you to move your limbs, you begin to see your own motives and desires as integral parts of the deterministic process. Your brain’s “algorithm” for deciding to apply to grad school, or to go for a run, or to call a friend, isn’t an optional “feature” that could be removed with no consequence. It’s how nature produces your next move.

Carl likened it to digestion: you can’t say, “Well, if I’m just a predetermined machine, I don’t need to secrete stomach acid.” That’s not how bodies work. Similarly, you can’t say, “If everything’s determined, I can skip forming intentions.” The very feeling of desire or will is part of the chain that leads from the present to the future. You’re not competing with determinism; you are a component of it.

I’d always pictured determination as a giant “puppet script,” with me as a character who had no real say in the plot. Carl’s post helped me see that my “say” in the plot is the plot. If I start practicing piano to get better, that is the causal engine for my becoming a better pianist. It’s not like the universe’s laws are going to “auto-play” my piano skills into existence if I don’t pick it up; they operate precisely through my brain’s decision-making.

Once you grasp that your urges and goals are the mechanism by which determined reality moves forward, it defangs the scariest part of the “it’s all predetermined” argument. You might still have philosophical questions about “could I have done otherwise?”—which I’ll explore later—but the immediate fear of “I’m out of control” dissolves. In truth, if you’re lying on the couch feeling unmotivated, that state isn’t automatically locked in by the universe. Your neural machinery can generate the desire to get up and do something—and that desire is exactly how the deterministic chain flows into the future you end up with. You can’t short-circuit it. It’s literally what produces your next action.

For many, this is enough to rescue them from the slump. Realizing that “I am the algorithm,” rather than “the algorithm is something done to me,” restores the sense that effort and drive genuinely matter. If your intentions disappear, so do the actions those intentions would have caused. If you lose willpower, you lose the outcomes willpower would have given you. Recognizing this can spark a renewed sense of responsibility for your life, paradoxically because your will is part of the natural world, not in spite of it.

Randomness Doesn’t Solve the “Free Will Problem” Either

A natural pushback when people first hear about determinism is, “But maybe the universe isn’t fully determined—what if there’s randomness or unpredictability involved?” It’s easy to imagine that if outcomes are not perfectly fixed, we’d feel more “free.” But even if elements of the universe are random, that doesn’t automatically grant you any greater control over your destiny. If your thoughts or actions partly hinge on a dice roll—whether at the quantum or classical level—how does that translate into you directing the show?

You can compare two universes:

Deterministic Universe: Everything runs like clockwork, from the Big Bang onward.

Stochastic Universe: It’s mostly deterministic, but sometimes genuine randomness—like dice rolls—kicks in to influence events.

In neither universe does randomness necessarily produce a more robust concept of free will. If, for instance, half your decisions are decided by a cosmic coin toss, do you actually feel more in control? Possibly not—your mental processes are now partially at the mercy of random noise. In a sense, that might make you less able to shape your own fate.

Some folks bring quantum mechanics into the discussion. They’ll say, “Well, quantum theory shows that outcomes can’t be perfectly predicted.” But as we’ll see more concretely in the next section—especially with the help of some figures that illustrate how “me” is within physics rather than competing with it—even quantum randomness doesn’t magically produce an agent that’s outside the laws of nature. Throwing dice into the equation doesn’t transform “I might do X” into a self-directed free choice; it just means there’s a small chance something else happens for no reason. That’s not obviously any more empowering.

In short, whether the universe is 100% deterministic or has pockets of randomness, the real crux of free will is about how your internal process—your “algorithm”—generates behavior. As a LW comment explains, “The question of meaning is orthogonal to whether we’re implemented predictably or unpredictably.” Even if half your neurons fired at random intervals, that wouldn’t confer more “freedom” on your mind. So while popular culture sometimes equates “randomness” with “freedom,” from a philosophical standpoint, it’s at best orthogonal—and at worst, it can undermine genuine control if your actions become more haphazard.

We Are *Inside* Physics

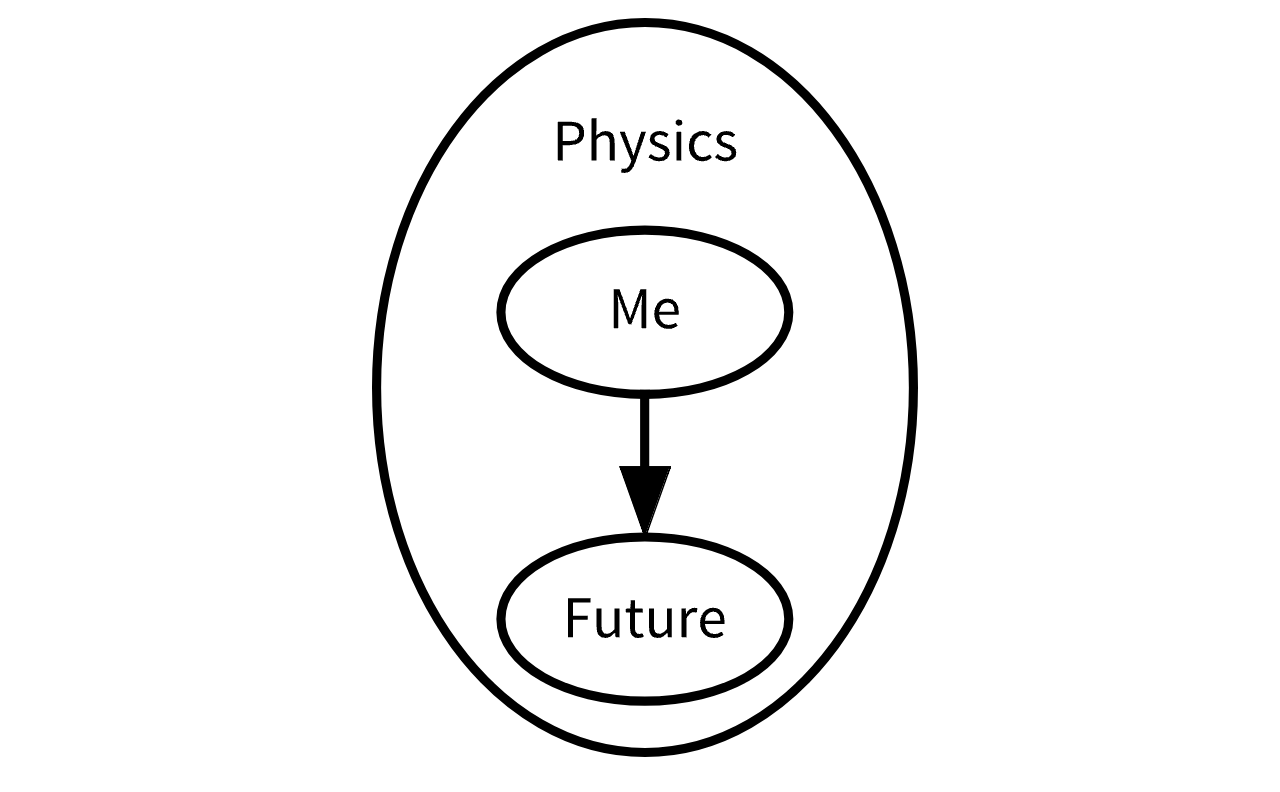

One of the simplest but most transformative ideas I came across in trying to reconcile free will and determinism came from Eliezer Yudkowsky: the notion that you’re not competing with physics but embedded in it. It’s so easy to fall into a mental model where we imagine:

“Physics” over here, shaping everything.

“Me” over there, trying (and presumably failing) to exert some separate influence on the future.

This picture above is wrong. A better diagram shows you as one of the physical forces shaping tomorrow's events.

The first framing incorrectly treats “Me” and “Physics” as two distinct causes vying for control of “Future.” The right side recognizes you’re a subset of physics. Your thoughts, desires, and plans are physical. No quarks or electrons have to “override” your intentions—your intentions themselves are part of this causal tapestry.

Why This Feels Liberating

You Don’t Compete With Determinism: Instead of thinking “the laws of nature are forcing me to do X,” it’s more accurate to say, “the laws of nature allow for a brain that processes goals, weighs moral considerations, and then does X.”

Agency Emerges Within Lawfulness: Yudkowsky dubs his position “Requiredism,” the idea that if you’re going to effectively steer the future at all, you need a lawful substrate in which mental effort can reliably lead to real-world results. If everything were random or chaotic, you couldn’t plan or act coherently.

You’re Still the Source of Your Actions: Even if we trace all actions back to physics, that chain includes your beliefs, experiences, and reasoning. So when you do something—like deciding to be kind or to exercise—it’s genuinely you doing it, in the sense that “you” is the localized process that leads from the present state to that outcome.

By adopting this internal view—“I am part of the physical story”—the notion of giving up because “physics is in charge” becomes as nonsensical as “I’ll stop playing soccer because the team is in charge.” You are on the team. Without your active participation, certain outcomes simply won’t happen. In other words, “determined by physics” translates to “determined by the full tapestry of influences,” and you’re a crucial thread in that tapestry. Letting go of your role is essentially letting go of the chain that leads from your intentions to future achievements. And that’s rarely something you’d want to do.

A Word on Moral Responsibility

I also realize many people care about free will because of moral responsibility: can we blame or praise someone if their actions follow from physical law? Under a compatibilist view, the answer is still "yes," because *how* you act depends on your internal reasoning and character. For example, if you choose kindness over cruelty, that arises from your capacity for moral reflection, empathy, or reasoning—physical law just explains *why* that reflection can yield different outcomes when your beliefs or values differ. We also shape each other's choices by praising good acts or condemning harm, and those social responses factor into future deliberations.

Critics of this view point to hard cases—instances of severe addiction, childhood trauma, or external manipulation—arguing that if these underlying causes were themselves determined, genuine accountability becomes impossible. But this challenge actually reveals the strength of compatibilism: it provides a framework to distinguish between actions flowing from someone's own reasoning and character (even if those were shaped by prior causes) versus cases where their normal decision-making process is impaired or bypassed. What matters isn't whether the choice was "uncaused," but whether it emerged from the person's own capacity for moral reasoning and response to reasons. This helps explain why we generally hold people accountable for considered choices while recognizing that certain circumstances can reduce or eliminate moral responsibility—all while staying within a deterministic framework.

So moral accountability still stands, not because we transcend the natural order but precisely because we inhabit it in a way that's sensitive to reasons and feedback.

The question of moral responsibility leads naturally to one of the deepest puzzles about free will and determinism: even if we accept that our choices matter and that we can be held accountable for them, many still wonder about the fundamental nature of choice itself. If our decisions emerge from physics, and physics follows unchangeable laws, what does it mean to say we "could have chosen differently"? This brings us to perhaps the most challenging aspect of reconciling free will with determinism.

Addressing “Could I have done otherwise?”

“But if I’m part of physics, could I have done otherwise?” That’s a thorny issue, but one partial answer is that we care more about how our brains handle alternatives in real time. Trying to do otherwise is itself a mental routine of weighing pros and cons, imagining scenarios, and eventually selecting one path. That routine is part of physics! So if, in the moment, you’re persuaded by new evidence or impulses, your choice can genuinely change. It’s just that this “change” is also embedded in the laws of nature.

Yudkowsky emphasizes we don’t even need deep quantum unpredictability here—our deliberations are how the future state of the world gets decided. Which is exactly the job we intuitively think of as “free will.” The mistake is imagining that for our free will to be “real,” it must break or transcend physics. But that would leave us with no stable mechanism to link our decisions to the real world. Contrarily, once you see your mind as a chunk of nature doing the deciding, there’s no contradiction.

Resolving Uneasiness About Counterfactual Control

One more exercise. We now see ourselves as inside physics. We are part of the causal chain. If you still don’t feel the intuition regarding counterfactuals, probably there is still a minor misunderstanding. If we say, “With the same initial conditions and the same laws of nature, would I inevitably make the same choice?” then sure—by definition, the answer is yes in a deterministic model. But if we ask in a more practical sense—“If I had different information or a different inclination, would I choose differently?”—that is precisely how decisions play out in our brains.

Imagine running a mental simulation: “If new evidence arose about a job offer, would that push me to accept it instead of decline?” The possibility that new information would sway your choice is a sign that your mind, operating within physical law, can respond to changes. So in a normal, everyday sense, we can do “otherwise”—if something relevant changes in our inputs or in the way we weigh them. That’s not contradictory. It just means our decision process is sensitive to variables that might shift.

In other words, your “capacity to do otherwise” corresponds to your ability to alter decisions in response to different reasons, rather than some spooky power to break out of physical cause-and-effect. And that capacity is precisely what we want when we talk about being rational, adaptable agents. Instead of undermining free will, determinism creates a stable framework in which “I can do otherwise if reasons change” is a real phenomenon.

Philosophers call this idea “compatibilism”—the claim that free will, properly understood, is compatible with determinism. Under that view, the fact that everything follows from something doesn’t mean your deliberation is pointless. It means your deliberation is how the next state of the world gets determined. The key is to understand that “could have done otherwise” isn’t about breaking physics but about how our decision-making depends on multiple potential reasons or pathways, and that if we had chosen differently, that, too, would be embedded in the chain of cause and effect.

Accepting Determinism and Owning Our Choices

If the idea of a lawful, determined universe once made you feel powerless—like your actions were just along for the ride—hopefully these perspectives offer some relief. Recognizing that:

Your motivations and intentions are indispensable parts of the causal chain,

Randomness wouldn’t magically give you more control, and

You’re not outside physics but a subset of it, steering the future via your mental processes,

can transform “I’m determined” from a defeatist statement into a simple recognition of how your agency emerges.

When you notice yourself debating, “Should I actually try at this?” remind yourself: if you don't try, who else will try in your place? The laws of nature won’t do it for you. Every step of effort, every moment of deliberation, is the machinery by which the future gets shaped. It’s only when we see our deliberations as some separate add-on that we feel overshadowed by “physics.” But from the inside, you are the piece of physics in charge of your next move.

Far from stripping away meaning from our actions, determinism provides the very framework through which our intentions shape reality. When you feel that creeping doubt about whether to act, remember: your impulse to "get out there and do something" isn't just an optional add-on—it's as fundamental to your nature as the chemistry of digestion, as essential as breathing. Your deliberations and choices are the universe's mechanism for writing tomorrow. And in this light, we find a profound truth: free will, properly understood, doesn't compete with physical law but emerges from it, flourishing precisely because we inhabit a lawful universe that transforms our intentions into reality.